Is steel, wood or concrete the most ‘green’ building material? (TVO.org)

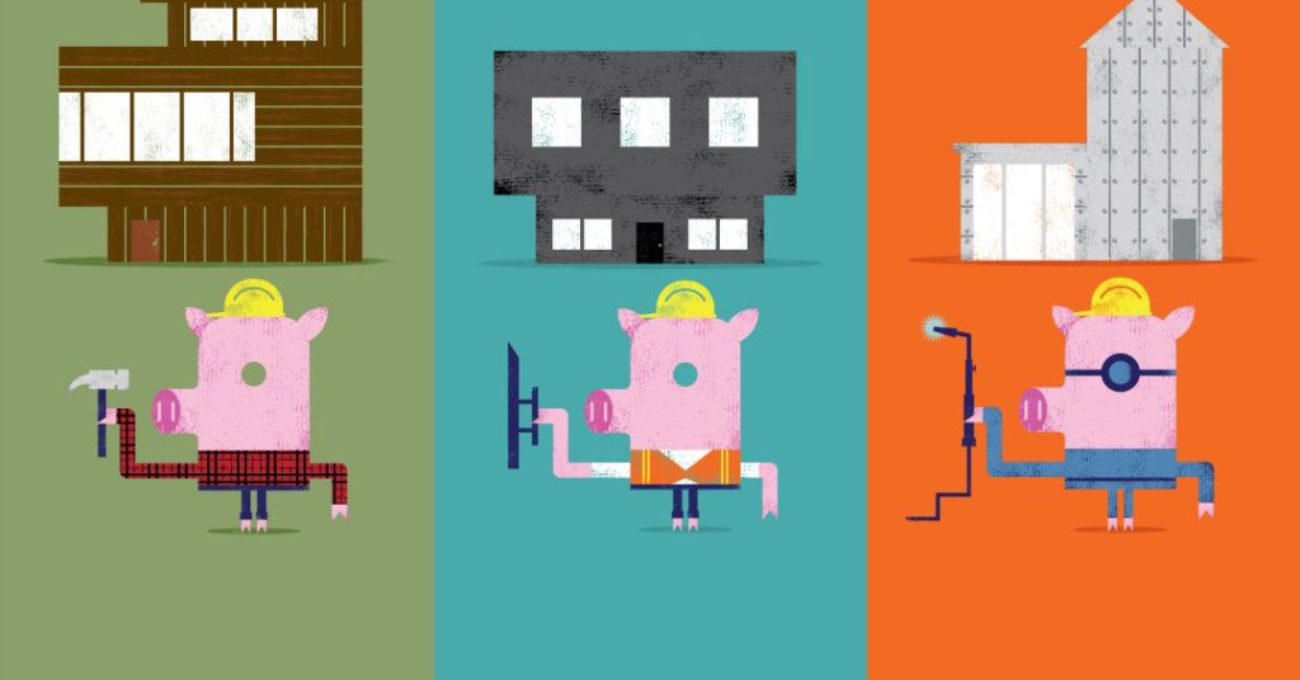

If the fairy tale of the Three Little Pigs were written today, the pigs’ homes would likely be built not out of straw, branches and bricks, but instead out of wood, steel and concrete. And the porky trio would be imperiled not by a big bad wolf, but by environmental cataclysm.

Any child reading the original story could tell you immediately that sticks and straw wouldn’t ever offer lupine stopping power, and that bricks were the obvious choice from the get-go. But it gets more complicated for modern builders trying to select materials based on what might save their ecological bacon.

Advocates for all three major construction materials lay claim to certain environmental merits. Steel can be essentially infinitely recycled and reused without degradation. Trees regrow, and lumber used in construction stores carbon dioxide. And new additives hold the potential to dramatically reduce concrete’s staggering carbon footprint.

“This is a longstanding battle between three main structural types in Canada,” says Terri Meyer Boake, professor of architecture at the University of Waterloo. “The environmental issues have just focused the arguments a little more, because they have actually something real to debate.”

Boake and many others say context matters in choice of materials, and that the impact of these materials is interrelated. Concrete, for instance, has fly ash in it, which is a byproduct of steelmaking. Ontario’s vibrant steel industry effectively makes both steel and concrete locally sourced materials in the province, but the same doesn’t hold true for, say, Quebec or B.C.

Not everyone sees the nuance, though.

“Wood is ahead of the other materials. Period,” says Marianne Berube, the director of Wood Works! Ontario, the provincial arm of a Canadian Wood Council campaign aimed at promoting wood use in construction. “Wood is the only renewable building product. You plant trees, grow, harvest and replant. Carbon is stored in buildings. It’s a huge benefit in climate change.”

She also points to technological advances like cross-laminated timber – a strong prefabricated material made by layering wood and adhesive – that makes wood viable for low-rise or even high-rise construction.

The University of British Columbia is building a record-setting 18-storey residence out of wood, and Vancouver architects are also involved in a project to create a wooden 35-floor mixed-use tower in Paris. Ontario recently changed its construction codes to allow six-storey wood buildings.

Boake agrees that cross-laminated timber and related wood products such as chipboard and laminated veneer lumber make wood a viable contender for green buildings. But she says claims that wood turns towers into global-warming-mitigating carbon sinks have to be evaluated carefully.

“If you leave the tree where it is, it’s not just storing carbon but also producing oxygen,” she says. And even though wood is inarguably reusable, that’s not the same as saying it is reused. “When you take down a building, you can salvage the wood, but I have not yet seen a house demolished that wasn’t demolished by a big backhoe. A lot of times they’ll just dump the wood.”

This explains why steel gets bragging rights as North America’s most recycled material. While wood is often thrown away and recycled concrete gets ground down into roadbed material, recovered steel retains its versatility.

“It doesn’t matter if the steel was a washing machine, a car or a building, it can be melted down and become whatever it needs to be,” Boake says. “When they make new steel from old, they might have to add alloys, but it’s never downcycled. It’s never, ‘We used this so many times we have to throw it out.’”

Still it’s worth remembering that of the three Rs of environmental stewardship, recycling is still more energy and resource intensive than reusing or reducing.

“Yes, steel is recyclable, but that recycling also has a carbon footprint,” says Janet Sumner, an environmental activist and the executive director of the Canadian Parks and Wildlands Services’ Wildlands League. “It all has to go to a recycling facility – which means there’s also transportation or haulage. But if it’s replacing the need for new steel, that’s probably going to have a smaller carbon footprint.”

Sumner spent a significant part of her career working on waste management, recycling and diversion projects. She says an organization like hers can only endorse the claims for a building material if they have complete and transparent data. While the calculations are complex, she finds it encouraging that these sectors are battling for ecological supremacy.

“What I do have is great hope,” she says. “It’s almost funny to see industries trying to outcompete each other on climate change. I’m now seeing proposals come across my desk saying, ‘We’re better,’ ‘No, we’re better.’ Some of it will be true, some won’t, but the fact that they are so motivated to be at the top of the class is staggering.”

For organizations like the Wildlands League, greenhouse gases are not the only consideration. Sumner’s equations also factor in issues such as biodiversity, health of native populations, and diversion of waste products created during resource production.

Even with all that complexity, everybody agrees on one thing:

“Concrete has a huge task on its hand,” Sumner says.

This single building material – the second-most consumed material on Earth after water – is responsible for between five and 10 per cent of all human-related greenhouse gases. Most of these emissions result from the production of cement – a key component of concrete. Cement holds together the sand and gravel that gives concrete its structure.

At Lakehead University, chemistry professor Stephen Kinrade has developed a remedy. He has found a “biosourced additive,” a polyol compound found in the waste stream of the pulp and paper industry that adds super-strength to a concrete mixture. Some simple math shows how this strength can be converted into kindness.

“Builders typically aren’t trying to make stronger concrete, but to build to specific requirements,” he says. “They have different specifications for a bridge, a sidewalk or a building wall. With this additive, they can meet those specifications by adding 25 to 40 per cent less cement to the concrete.”

Kinrade says the science is solid, but that getting the additive into widespread use has been more of a challenge than he expected.

“The building industry is hyper-conservative,” he says. “The piggies are building their house to last for a hundred years. They are very reluctant to try new things, because they have technology that works.”

Concrete, for instance, is commonly reinforced with steel rebar. Steel survives well in concrete’s alkaline embrace. The building industry is leery of recipe changes for fear of introducing rebar-rotting acidity into the mix.

Kinrade’s research has concluded that his additive doesn’t affect alkalinity or any other relevant chemistry. Still, he continues to work to assuage the industry’s concerns, examining things like the microstructures where the gravel and sand meet the cement to ensure that reducing carbon emissions comes at no cost to structural strength and durability.

No single construction material is likely to outpace the others as the building industry’s silver bullet. In fact, the three main materials will likely only become more interconnected.

“Globally, there are a lot of collaborations between steel, concrete and wood industries to create hybrid technologies,” says Mohini Sain, an engineer and materials scientist professor at the University of Toronto. “Steel and concrete already join hands to create buildings that are 100 or 120 floors. But we could see wood laminates with steel as reinforcement. At U of T, we’ve been doing significant research in concrete and solid wood.”

High-tech eco-friendly hybrid materials might themselves seem to be the stuff of fairy tales, but with climate change’s hot breath already huffing and puffing at our door, they may be our best chance to live happily ever after.

Journalist and author Patchen Barss has written, edited and produced stories about science, research and culture for more than 20 years.