A moment of silence, a glimpse inside a black hole, and the Nobel Prize

(BBC) On a crisp September day in 1964, Roger Penrose had a visit from an old friend. The British cosmologist Ivor Robinson was back in England from Dallas, Texas, where he lived and worked. Whenever the two met up, they never lacked for conversation, and their talk on this occasion was non-stop and wide ranging.

As the pair walked near Penrose’s office at Birkbeck College in London, they paused briefly on the kerb, waiting for a break in the traffic. The momentary halt in their stroll coincided with a lull in conversation and they fell into silence as they crossed the road.

In that moment, Penrose’s mind drifted. It travelled 2.5 billion light years through the vacuum of outer space to the seething mass of a whirling quasar. He imagined how gravitational collapse was taking over, pulling an entire galaxy in deeper and closer to the centre. Like a twirling figure skater pulling their arms in close to their body, the mass would spin more and more quickly as it contracted.

This brief mental flicker led to a revelation – one that 56 years later would win him the Nobel Prize in Physics.

Like many relativists — theoretical physicists working to test, explore and extend Albert Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity — Penrose had spent the early 1960s studying a strange, but particularly knotty contradiction known as “the singularity problem”.

Einstein published his General Theory in 1915, revolutionising scientists’ understanding of space, time, gravity, matter and energy. By the 1950s, Einstein’s theory was wildly successful, but many of its predictions were still regarded as improbable and untestable. His equations showed, for instance, that it was theoretically possible for gravitational collapse to force enough matter into a sufficiently small region that it would become infinitely dense, forming a “singularity” from which not even light could escape. These became known as black holes.

But within such a singularity, the known laws of physics — including Einstein’s own theory of relativity that predicted it — would no longer apply.

Singularities were fascinating to mathematical relativists for this very reason. Most physicists, however, agreed our Universe was too orderly to actually contain such regions. And even if singularities did exist, there would be no way to observe them.

“There was huge scepticism for a long time,” says Penrose. “People expected there to be a bounce: that an object would collapse and swirl around in some complicated way, and come swishing back out again.”

In the late 1950s, observations from the emerging field of radio astronomy threw these ideas into turmoil. Radio astronomers detected new cosmic objects that appeared to be very bright, very distant and very small. First known as “quasi-stellar objects” – later shortened to “quasars” – these objects appeared to exhibit too much energy in too small a space. While it seemed impossible, every new observation pointed toward the idea that quasars were ancient galaxies in the process of collapsing into singularities.

Scientists were forced to ask themselves whether singularities were not as unlikely as everyone thought? Was this prediction of relativity more than just a mathematical flight of fancy?

In Austin, Princeton, and Moscow, at Cambridge and Oxford, in South Africa, New Zealand, India, and elsewhere, cosmologists, astronomers, and mathematicians scrambled to find a definitive theory that could explain the nature of quasars.

Most scientists approached the challenge by trying to identify highly specialised circumstances under which a singularity might form.

Penrose, then a reader at Birkbeck College in London, took a different approach. His natural instinct had always been to search for general solutions, underlying principles and essential mathematical structures. He spent long hours at Birkbeck, working at a large chalkboard covered in curves and twists of diagrams of his own design.

In 1963, a team of Russian theorists led by Isaac Khalatnikov published an acclaimed paper that confirmed what most scientists still believed – singularities were not a part of our physical Universe. In the Universe, they said, collapsing dust clouds or stars would indeed expand back out again long before they reached the point of singularity. There had to be some other explanation for quasars.

Penrose was sceptical.

“I had the strong feeling that with the methods they were using, it was unlikely they could have come to a firm conclusion about it,” he says. “It seemed to me the problem needed to be looked at in a more general way than they were doing, which was a somewhat limited focus.”

Still, while he rejected their arguments, he still could not develop a general solution for the singularity problem. That was until the visit by Robinson. Although Robinson too was researching the singularity problem, the pair didn’t discuss it during their conversation on that autumn day of 1964 in London.

During the brief quiet of that fateful street crossing, however, Penrose realised that the Russians were wrong.

All of that energy, movement and mass shrinking together would create a heat so intense that radiation would blast out on every wavelength in every direction. The smaller and faster it got, the brighter it would glow.

He mentally mapped his chalkboard drawings and journal sketches onto that distant object, searching his mind for the point the Russians’ predicted, where this cloud would explode back out again.

No such point existed. In his mind’s eye, Penrose at last saw how the collapse would continue unimpeded. Outside the densifying centre, the object would shine with more light than all the stars in our galaxy. And deep within, light would bend at dramatic angles, spacetime warping until every direction converged on every other.

There would come a point of no return. Light, space and time would all come to a full stop. A black hole.

At that moment, Penrose knew a singularity didn’t require any special circumstances. In our Universe, singularities weren’t impossible. They were inevitable.

Back on the other side of the street, he picked up his conversation with Robinson, and immediately forgot what he had been thinking about. They bid farewell, and Penrose returned to the chalk clouds and stacks of paper in his office.

The rest of the afternoon went as normal, except Penrose found himself in an inordinately good mood. He could not figure out why. He began reviewing his day, investigating what might be powering his euphoria.

His mind returned to that moment of silence crossing the street. And it all came flooding back. He had solved the singularity problem.

He began writing down equations, testing, editing, rearranging. The argument was still rough, but it all worked. A gravitational collapse required only some very general, easy-to-meet energy conditions, to collapse into infinite density. Penrose knew at that moment there had to be billions of singularities littering the cosmos.

It was an idea that would upend our understanding of the Universe and shape what we now know about it today.

Within two months, Penrose had begun giving talks on the theorem. In mid-December, he submitted a paper to the academic journal Physical Review Letters, which was published on 18 January 1965 – just four months after he crossed the street with Ivor Robinson.

The response was not quite what he hoped. The Penrose Singularity Theorem was debated. Refuted. Contradicted.

The debate came to a head at the International Congress on General Relativity and Gravity in London later that year.

“It was not very friendly. The Russians were pretty annoyed, and people were reluctant to admit they were mistaken,” says Penrose. The conference ended with the debate unresolved.

But not long after, it came out that the Russian paper had errors in its calculations – the mathematics was fatally flawed, their thesis no longer tenable.

“There was an error in the way they were doing it,” says Penrose.

By late 1965, the Penrose Singularity Theorem was gaining traction all over the world. His singular flash of insight became a driving force in cosmology. He had done more than explain what a quasar was – he had revealed a major truth about the underlying reality of our Universe. Whatever models of the Universe people came up with from then on had to include singularities, which meant including science that goes beyond relativity.

Singularities also began to seep into the public consciousness, thanks partly to their becoming known evocatively as “black holes”, a term first used publicly by American science journalist Ann Ewing.

Stephen Hawking famously built on Penrose’s theorem to upend theories about the origin of the Universe after the pair worked together on singularities. Singularities became central to every theory about the nature, history and future of the Universe. Experimentalists identified other singularities – including the one at the heart of the hypermassive black hole at the centre of our own galaxy discovered by Reinhard Genzel and Andrea Ghez, who shared the Nobel Prize in Physics with Penrose this year.

Penrose himself went on to develop an alternative to the Big Bang Theory known as Conformal Cyclic Cosmology, the evidence for which could come from the remnant signals from ancient black holes.

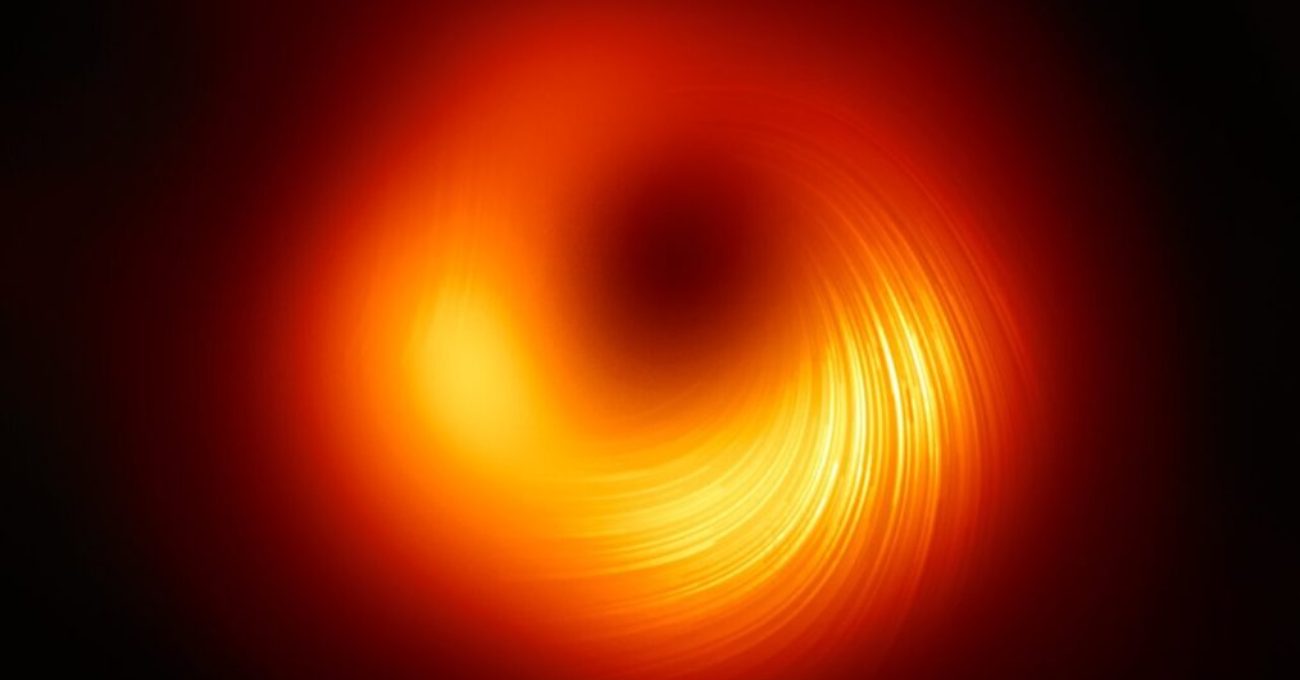

In 2013, engineer and computer scientist Katie Bouman led a team of researchers which developed an algorithm that they hoped would allow black holes to be photographed. In April 2019, the Event Horizons telescope used that algorithm to capture the first images of a black hole, providing dramatic visual confirmation of both Einstein’s and Penrose’s once controversial theories.

While Penrose, now 89 years old, is pleased to have been awarded the highest honour in physics, the Nobel Prize, but there is something else pressing on his mind.

“It feels weird. I’ve just been trying to adjust myself. It’s very flattering and a huge honour and much appreciated,” he tells me a few hours after receiving the news. “But on the other hand, I am trying to write three different (scientific) articles at the same time, and this makes it harder than it was before.” The phone, he explains, hasn’t stopped ringing with people congratulating him and journalists asking for interviews. And all that clamour is distracting him from focusing on his latest theories.

Penrose knows better than anyone the power of silence and the flash of insight it can deliver.